Pancreatic Cancers

The pancreas, located in the abdomen, has cells with endocrine (hormonal) and exocrine (digestive) functions;cancer cells can develop from both types of functional cells.

Most pancreatic cancers are adenocarcinomas.

Few patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer have identifiable risk factors.

Pancreatic cancer is highly lethal because it grows and spreads rapidly and often in its late stages.

Genetic analysis has recently identified four pancreatic cancer subtypes -- squamous, pancreatic progenitor, aberrantly differentiated endocrine exocrine (ADEX), and immunogenic.

Pancreatic cancer may be difficult to diagnose until late in its course. Symptoms and signs of pancreatic cancer in its late stage include weight loss and back pain. In some cases, painle jaundice may be a symptom of early pancreatic cancer that can be cured with surgery.

The only curative treatment is surgical removal of all cancer, occasionally removal of the

entire pancreas, and a pancreatic transplant; however, few patients are eligible for a

pancreatic transplant.

Chemotherapy after surgery can lower the chances of the cancer returning.

Chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer can extend life and improve the quality of life,

but it rarely cures the patient.

Patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer are encouraged to seek out clinical trials that will

ultimately improve pancreatic cancer treatment.

Many organizations exist to help provide information and support for patients and families fighting pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic Cancer Symptoms

Pancreatic cancer typically does not cause symptoms until it has grown, so it is most frequently diagnosed in advanced stages rather than early in the course of the disease. In some cases, jaundice (a yellowish discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes) without pain can be an early sign of pancreatic cancer. Other symptoms that can occur with more advanced disease are:

nausea,

vomiting,

weight loss,

itching skin, and

decreased appetite.

Pale stools, back pain, abdominal pain, dark urine, abdominal bloating, diarrhea, and enlarged lymph nodes in the neck can be present as well.

What does a pancreas do?

The pancreas is an organ in the abdomen that sits in front of the spine above the level of the belly button. It performs two main functions:

first, it makes insulin, a hormone that regulates blood sugar levels (an endocrine function); and

second, it makes and secretes into the intestine digestive enzymes which help break down dietary proteins,fats, and carbohydrates (an exocrine function).

The enzymes help digestion by chopping proteins, fats, and carbohydrates into smaller parts so that they can be more easily absorbed by the body and used as building blocks for tissues and for energy. Enzymes leave the pancreas via a system of tubes called "ducts" that connect the pancreas to the intestines where the enzymes mix with ingested food.

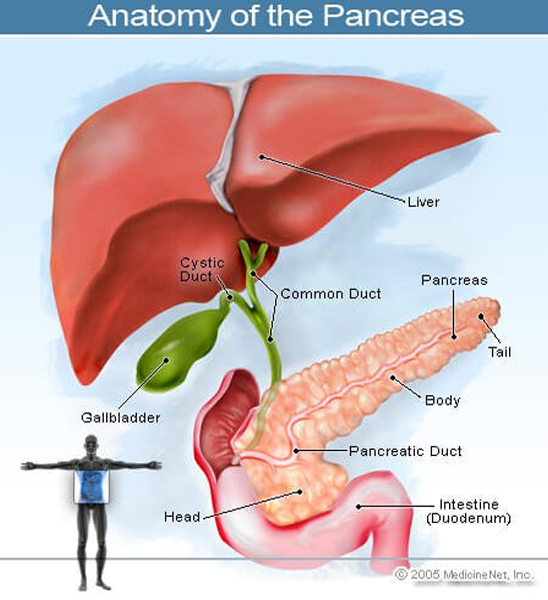

The pancreas sits deep in the abdomen and is in close proximity to many important structures such as the small intestine (the duodenum) and the bile ducts, as well as important blood vessels and nerves.

Cancer that starts in the pancreas is called pancreatic cancer. This picture of the pancreas shows its location in the back of the abdomen, behind the stomach.

What is cancer?

Every second of every day within our body, a massive process of destruction and repair occurs. The human body is made up of trillions of cells and every day billions of cells wear out or are destroyed. Each time the body makes a new cell to replace one that is wearing out, the body tries to make a perfect copy of the cell that dies off, usually by having similar healthy cells divide into two cells because that dying cell had a job to do, and the newly made cell must be capable of performing that same function. Despite remarkably elegant systems in place to edit out errors in this process, the body makes tens of thousands of mistakes daily in normal cell division either due to random errors or from environmental pressure within the body. Most of these mistakes are corrected, or the mistake leads to the death of the newly made cell, and another new cell then is made. Sometimes a mistake is made that, rather than inhibiting the cell's ability to grow and survive, allows the newly made cell to grow in an unregulated manner. When this occurs, that cell becomes a cancer cell able to divide independent of the checks and balances that control normal cell division. The cancer cell multiplies, and a cancerous or malignant tumor develops.

Tumors fall into two categories:"benign" tumors and "malignant", or cancerous, tumors. So what is the difference? The answer is that a benign tumor grows only in the tissue from which it arises. Benign tumors sometimes can grow quite large or grow rapidly and cause severe symptoms. For example, a fibroid in a woman's uterus can cause bleeding or pain, but it will never travel outside the uterus, invade surrounding tissues or grow as a new tumor elsewhere in the body (metastasized). Fibroids, like all benign tumors, lack the capacity to shed cells into the blood and lymph systems and cannot travel to other places in the body and grow. A cancer, on the other hand, can shed cells from the original tumor that can float like dandelion seeds in the wind through the bloodstream or lymphatics, landing in tissues distant from the tumor, developing into new tumors in other parts of the body. This process, called metastasis, is the defining characteristic of a cancerous tumor. Pancreatic cancer, unfortunately, is a particularly good model for this process. Pancreatic cancers can metastasize early to other organs in this manner. They also can grow and invade adjacent structures directly, often rendering the surgical removal of the tumor impossible.

Cancers are named by the tissues from which the primary tumor arises. Hence, a lung cancer that travels to the liver is not a "liver cancer" but is described as metastatic lung cancer and a patient with a breast cancer that spreads to the brain is not described as having a brain tumor"; but rather as having metastatic breast cancer.

What is pancreatic cancer? What are the types of pancreatic cancer?

A cancers that develops within the pancreas falls into two major categories: (1) cancers of the endocrine pancreas (the part that makes insulin and other hormones) are called; "islet cel"; or "pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors or PNETs" and (2) cancers of the exocrine pancreas (the part that makes enzymes). Islet cell cancers are rare and typically grow slowly compared to exocrine pancreatic cancers.Islet cell tumors often release hormones into the bloodstream and are further characterized by the hormones they produce (insulin, glucagon, gastrin, and other hormones). Cancers of the exocrine pancreas (exocrine cancers) develop from the cells that line the system of ducts that deliver enzymes to the small intestine and are commonly referred to as pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Squamous cell pancreatic cancer is rare. Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas comprises most all pancreatic ductal cancers and is the main subject of this review.

Cells that line the ducts in the exocrine pancreas divide more rapidly than the tissues that surround them. For reasons that we do not understand, these cells can make a mistake when they copy their DNA as they are dividing to replace other dying cells. In this manner, an abnormal cell can be made. When an abnormal ductal cell begins to divide in an unregulated way, a growth can form that is made up of abnormal looking and functioning cells. The abnormal changes that can be recognized under the microscope are called; "dysplasia." Often, dysplastic cells can undergo additional DNA mistakes over time and become even more abnormal. When these dysplastic cells invade through the walls of the duct from which they arise into the surrounding tissue, the dysplasia has become a cancer.

In a study published in 2016, researchers reported analysis of the genes in 456 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Subsequent expression analysis of these adenocarcinomas allowed them to be defined into four subtypes. These subtypes have not been previously discerned. The subtypes include:

Squamous: These tumors have enriched TP53 and KDMA mutations.

Pancreatic progenitor: These tumors express genes involved in pancreatic development such as FOXA2/3, PDX1, and MNX1.

Aberrantly differentiated endocrine exocrine (ADEX): These tumors display the genes (KRAS) and exocrine (NR5A2 and RBPJL) plus endocrine (NEUROD1 and NKX2-2) differentiation.

Immunogenic: These tumors contain pathways that are involved in acquired immune suppression.

These new findings may allow future patients to be treated more specifically depending on their subtype and, hopefully, more effectively. For example, the immunogenic subtype could possibly respond to therapy where the immune system is re-engineered to attack these types of cancer cells.

Pancreatic cancer should not be confused with the termpancreatitis. Pancreatitis is simply defined as inflammation of the pancreas and is mainly caused by alcohol abuse and /or gallstone formation (about 80% to 90%). Nevertheless,chronic pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic cancer.

What are pancreatic cancer causes and risk factors?

Most people who develop pancreatic cancer do so without any predisposing risk factors. However, perhaps the biggest risk factor is increasing age; being over the age of 60 puts an individual at greater risk. Rarely, there can be familial or hereditary genetic syndromes arising from genetic mutations that run in families and put individuals at higher risk, such as BRCA-2 and, to a lesser extent, BRCA-1 gene mutations. Familial syndromes are unusual, but it is important to let a doctor know if anyone else in the family has been diagnosed with cancer, especially pancreatic cancer. Additionally, certain behaviors or conditions are thought to slightly increase an individual's risk for developing pancreatic cancer. For example, African-Americans may be at greater risk as may individuals with close family members who have been previously diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Other behaviors or conditions that may put people at risk include tobacco use,obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, a history of diabetes, chronic pancreatic inflammation (pancreatitis), and a fatty (or Western)diet. Prior stomach surgery may moderately increase one's risk as can certain chronic infections such as hepatitis B and H.pylori (a bacterial infection of the stomach lining). Certain drugs ( sitagliptin[ Januvia ] and metformin and sitagliptin [ Janumet ]) have been linked to the development of pancreatic cancer. Some types of pancreatic cysts may put individuals at risk of developing pancreatic cancer. When pancreatic cancer begins, it usually starts in the cells that line the ducts of the pancreas and is termedpancreatic adenocarcinoma orpancreatic exocrine cancer. Despite the associated risks cited above, no identifiable cause is found in most people who develop pancreatic cancer.

What are pancreatic cancer symptoms and signs?

Because the pancreas lies deep in the belly in front of the spine, pancreatic cancer often grows silently for months before it is discovered. Early symptoms and/or first signs can be absent or quite subtle. More easily identifiable symptoms develop once the tumor grows large enough to press on other nearby structures, such as nerves (which causes pain), the intestines (which affects appetite and causes nausea along with weight loss), or the bile ducts (which causes jaundice or a yellowing of the skin and can cause loss of appetite and itching). Symptoms in women rarely differ from those in men. Once the tumor sheds cancer cells into the blood and lymph systems and metastasizes, additional symptoms usually arise, depending on the location of the metastasis. Frequent sites of metastasis for pancreatic cancer include the liver, the lymph nodes, and the lining of the abdomen (called the peritoneum). Unfortunately, most pancreatic cancers are found after the cancer has grown or progressed beyond the pancreas or has metastasized to other places.

In general, the signs andsymptoms of pancreatic cancer can be produced by exocrine or endocrine cancer cells. Many of the signs and symptoms of exocrine pancreatic cancer result from blockage of the duct that travels through the pancreas from the liver carrying bile to the intestine. Symptoms of exocrine pancreatic cancer include

jaundice,

dark urine,,

itchy, skin

light-colored stools

pain in the abdomen or the back,

poor appetiteandor weight loss,

digestive problems (pale and/or greasy stools, nausea, and vomiting),

blood clots, and

enlarged gallbladder.

The signs and symptoms of endocrine pancreatic cancers are often related to the excess hormones

that they produce and consequently to a variety of different symptoms. Such symptoms are related to

the hormones and are as follows:

Insulinomas: Insulin-producing tumors that lower blood glucose (sugar) levels can cause low

blood sugars that result in weakness, confusion, coma, and even death.

Glucagonomas: Glucagon-producing tumors can increase glucose levels and

cause symptoms of diabetes (thirst, increased urination, diarrhea and skin changes,

especially a characteristic rash termed necrolytic migratory erythema).

Gastrinomas: Gastrin-producing tumors trigger the stomach to produce too much acid, which leads to ulcers, black tarry stools, and anemia

Somatostatinomas: Somatostatin-producing tumors result in other hormones being

overregulated and producing symptoms of diabetes, diarrhea, belly pain, jaundice, and

possibly other problems.

VIPomas: These tumors produce a substance called vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) that may cause severe watery diarrhea and digestive problems along with high blood glucose levels.

PPomas: These tumors produce pancreatic polypeptide (PP) that affects both endocrine and exocrine functions, resulting in abdominal pain, enlarged livers, and watery diarrhea.

Carcinoid tumors: These tumors make serotonin or its precursor, 5-HTP, and may cause

the carcinoid syndrome with symptoms of flushing of the skin, diarrhea,wheezing, and a rapid

heart rate that occurs episodically; eventually, a heart murmur, shortness of breath, and

weakness develop due to damage to the heart valves.

Nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors don't make excess hormones but can grow large and spread out of the pancreas. Symptoms then can be like any of the endocrine pancreatic cancers described above.

How is the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer made?

Most people do not need to be screened for pancreatic cancer, and the tests available for screening frequently are complex, risky, expensive, or insensitive in the early phases of the cancer. Those who may qualify usually have a set of factors that increase the risk for pancreatic cancer, such as pancreatic cysts, first-degree relatives with pancreatic cancer, or a history of genetic syndromes associated with pancreatic cancer. Most screening tests consist of CT scans, ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), or endoscopic ultrasounds.

Most people with pancreatic cancer first go to their primary-care doctor complaining of nonspecific symptoms (see symptoms section above). Some warning signs include pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, weight loss,fatigue, and increased abdominal fluid. These complaints trigger an evaluation often including a physical examination (usually normal), blood tests, X-rays, and an ultrasound. If pancreatic cancer is present, the likelihood of an ultrasound revealing an abnormality in the pancreas is about 75%. If a problem is identified or suspected, frequently a computed tomography (CT) scan is performed as the next step in the evaluation; some clinicians prefer an MRI. If a pancreatic mass is seen, that raises the suspicion of pancreatic cancer and a doctor then performs a biopsy to yield a diagnosis.

Different strategies can be used to perform a biopsy of the suspected cancer. Often, a needle biopsy of the liver through the belly wall (percutaneous liver biopsy) will be used if it appears that there has been spread of the cancer to the liver. If the tumor remains localized to the pancreas, biopsy of the pancreas directly usually is performed with the aid of a CT. A direct biopsy also can be made via an endoscope put down the throat and into the intestines. A camera on the tip of the endoscope allows the endoscopist to advance the endoscope within the intestine. An ultrasound device at the tip of the endoscope locates the area of the pancreas to be biopsied, and a biopsy needle is passed through a working channel in the endoscope to obtain tissue from the suspected cancer. Ultimately, a tissue diagnosis is the only way to make the diagnosis with certainty, and the team of doctors works to obtain a tissue diagnosis in the easiest way possible.

In addition to radiologic tests, suspicion of a pancreatic cancer can arise from the elevation of a "tumor marker", a blood test which can be abnormally high in people with pancreatic cancer. The tumor marker most commonly associated with pancreatic cancer is called the CA 19-9. It often is released into the bloodstream by pancreatic cancer cells and may be elevated in patients newly found to have pancreatic cancer. Unfortunately, although the CA 19-9 test is cancer-related, it is not specific for pancreatic cancer. Other cancers as well as some benign conditions can cause the CA 19-9 to be elevated. Sometimes (about 20% of the time) the CA 19-9 will be at normal levels in the blood despite a confirmed diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, so the tumor marker is not perfect. It can be helpful, however, to follow during the course of illness since its rise and fall may correlate with the cancer's growth and help guide appropriate therapy.

How do health care professionals determine the stage of pancreatic cancer?

Once pancreatic cancer is diagnosed, it is "staged". Pancreatic cancer is broken into four stages with stage 1 being the earliest stage (stage 0 is not counted) and stage IV being the most advanced (metastatic disease). The following are the stages of pancreatic cancer according to the National Cancer Institute:

Stage 0: Cancer is found only in the lining of the pancreatic ducts. Stage 0 also is called carcinoma in situ.

Stage I: Cancer has formed and is in the pancreas only.

Stage IA: The tumor is 2 centimeters or smaller.

Stage IB: The tumor is larger than 2 centimeters.

Stage II: Cancer may have spread or advanced to nearby tissue and organs and lymph nodes near the pancreas.

Stage IIA: Cancer has spread to nearby tissue and organs but has not spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage IIB: Cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes and may have spread to other nearby tissue and organs.

Stage III: Cancer has spread or progressed to the major blood vessels near the pancreas and may have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage IV: Cancer may be of any size and has spread to distant organs, such as the liver, lung, and peritoneal cavity. It also may have spread to organs and tissues near the pancreas or to lymph nodes. This stage has also been termed end stage pancreatic cancer.

Unlike many cancers, however, patients with pancreatic cancer are typically grouped into three categories, those with local disease, those with locally advanced, unresectable disease, and those with metastatic disease. Initial therapy often differs for patients in these three groups.

Patients with stage I and stage II cancers are thought to have local or "resectable"; cancer (cancer that can be completely removed with an operation). Patients with stage III cancers have "locally advanced, unresectable" disease. In this situation, the opportunity for cure has been lost but local treatments such as radiation remain options. In patients with stage IV pancreatic cancer, chemotherapy is most commonly recommended as a means of controlling the symptoms related to the cancer and extending life. Below, we will review common treatments for the three groups of pancreatic cancers (resectable, locally advanced unresectable, and metastatic pancreatic cancer).

What is the treatment for resectable pancreatic cancer?

If a pancreatic cancer is found at an early stage (stage I and stage II) and is contained locally within or around the pancreas, surgery may be recommended (resectable pancreatic cancer). Surgery is the only potentially curative treatment for pancreatic cancer. The surgical procedure most commonly performed to remove a pancreatic cancer is a Whipple procedure (pancreatoduodenectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy). It often comprises removal of a portion of the stomach, the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine), pancreas, a portion of the main bile duct, lymph nodes, and gallbladder. It is important to be evaluated at a hospital with lots of experience performing pancreatic cancer surgery because the operation is a big one, and evidence shows that experienced surgeons better select people who can get through the surgery safely and also better judge who will most likely benefit from the operation. In experienced hands, the mortality from the surgery itself is less than 4%.

After the Whipple surgery, patients typically spend about one week in the hospital recovering from the operation. Complications from the surgery can include blood loss ( anemia ), leakage from the reconnected intestines or ducts, or slow return of bowel function. Recovery to presurgical health often can take several months.

After patients recover from a Whipple procedure for pancreatic cancer, treatment to reduce the risk of the cancer returning is a standard recommendation. This treatment, referred to as "adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy)," has proven to lower the risk of recurrent cancer. Typically 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended, sometimes with radiation incorporated into the treatment plan.

Unfortunately, only about 20 people out of 100 diagnosed with pancreatic cancer are found to have a tumor amenable to surgical resection. The rest have tumors that are too locally advanced to completely remove or have metastatic spread at the time of diagnosis. Even among patients whose cancers are amenable to surgery, statistical data suggest that only 20% live 5 years. Most pancreatic cancer patients do not qualify for a pancreas transplant because of their advanced disease; most pancreas transplants are done in patients with diabetes that results from the removal of the endocrine portion of the pancreas and not for pancreatic cancer.

What is the treatment for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer?

If a pancreatic cancer is found when it has grown into important local structures but not yet spread to distant sites, this is described as locally advanced, unresectable (inoperable) pancreatic cancer (stage III). The treatment of locally advanced cancer is a combination of low-dose chemotherapy given simultaneously with radiation treatments to the pancreas and surrounding tissues. Radiation treatments are designed to lower the risk of local growth of the cancer, thereby minimizing the symptoms that local progression causes (back or belly pain, nausea, loss of appetite, intestinal blockage, jaundice). Radiation treatments are typically given Monday through Friday for about 5 weeks. Chemotherapy given concurrently (at the same time) may improve the effectiveness of the radiation and may lower the risk for cancer spread outside the area where the radiation is delivered. When the radiation is completed and the patient has recovered, more chemotherapy often is recommended. Recently, newer forms of radiation delivery (stereotactic radiosurgery, gamma knife radiation, cyber knife radiation) have been utilized in locally advanced pancreatic cancer with varying degrees of success, but these treatments can be more toxic and are, for now, largely experimental.

What is the treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer?

Once a pancreatic cancer has spread beyond the vicinity of the pancreas and involves other organs, it has become a problem through the system. As a result, a systemic treatment is most appropriate and chemotherapy (for example, protein-bound paclitaxel [Abraxane] in combination with gemcitabine [ Gemzar ]) is recommended. Chemotherapy travels through the bloodstream and goes anywhere the blood flows and, as such, treats most of the body. It can attack a cancer that has spread through the body wherever it is found. In metastatic pancreatic cancer, chemotherapy is recommended for individuals healthy enough to receive it. It has been proven to both extend the lives of patients with pancreatic cancer and to improve their quality of life. These benefits are documented, but unfortunately the overall benefit from chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer treatment is modest and chemotherapy prolongs life for the average patient by only a few months. Chemotherapy options for patients with pancreatic cancer vary from treatment with a single chemotherapy agent to treatment with as many as three chemotherapy agents given together. The aggressiveness of the treatment is determined by the cancer doctor (medical oncologist) and by the overall health and strength of the individual patient.

What are the side effects of pancreatic cancer treatment?

Side effects of treatment for pancreatic cancer vary depending on the type of treatment. For example, radiation treatment (which is a local treatment) side effects tend to accumulate throughout the course of radiation therapy and include fatigue, nausea, and diarrhea. Chemotherapy side effects depend on the type of chemotherapy given (less aggressive chemotherapy treatments typically cause fewer side effects whereas more aggressive combination regimens are more toxic) and can include fatigue, loss of appetite, change in taste, hair loss (although not usually), and lowering of the immune system with risk for infections (immunosuppression). While these lists of side effects may seem worrisome, radiation doctors (radiation oncologists) and medical oncologists have much better supportive medications than they did in years past to control any nausea, pain, diarrhea, or immunosuppression related to treatment. The risks associated with pancreatic cancer treatment must be weighed against the inevitable and devastating risks associated with uncontrolled pancreatic cancer and, if the treatments control progression of the cancer, most patients feel better on treatment than they otherwise would.

What is the survival rate with pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic cancer is a difficult disease. Even for surgically resectable (and therefore potentially curable) tumors, the risk of cancer recurrence and subsequent death remains high. Consequently, the prognosis of pancreatic cancer usually ranges from fair to poor. Only about 20% of patients undergoing a Whipple procedure for potentially curable pancreatic cancer live five years, with the rest surviving on average less than two years. For patients with incurable (locally advanced unresectable or metastatic) pancreatic cancer, survival is even shorter; typically, it is measured in months. With metastatic disease (stage IV), the average survival is just over six months. The American Cancer Society statistics suggest that for all stages of pancreatic cancer combined, the one-year survival rate is 20% and the mortality rate is 80%, while the five-year survival rate is 6% with a mortality rate of 94%. These rates are mainly based on patients diagnosed between 1985 and 2004 and are representative of those patients according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). These data-based survival rates are what are available currently, but they are only estimates and are not predictive about what may happen to each individual. Currently, the ACS advises patients to discuss their individual situation and prognosis with their treatment team of physicians. Doctors around the world continue to study pancreatic cancer and strive to improve treatments, but progress has been difficult to achieve.

What research is being done on pancreatic cancer?

Doctors and researchers all over the world are hard at work developing better treatments for pancreatic cancer. Cooperative cancer research led by centers of excellence in this country and many others continue daily to test new surgical techniques, radiation strategies, chemotherapy agents, and alternative therapies in an effort to improve care. Given the slow progress experienced over the last quarter century, many doctors feel that every eligible patient with pancreatic cancer should be offered enrollment in a research trial. New cytotoxic combinations of drugs are being tried in clinical trials. For example, Folfirinox, a new combination regimen consisting of four different chemicals has shown increased survival times for patients in clinical trials. In addition, patients who received one of two vaccines, GVAX and CRS-207, showed about a doubling of survival time compared to patients that did not receive the vaccine; this vaccine protocol is still undergoing clinical trials. For a complete list of clinical trials in pancreatic cancer treatment, please check online at http://www.cancer.gov.

Is complimentary or alternative medicine effective in pancreatic cancer treatment?

Complimentary or alternative medicine is of unclear benefit in pancreatic cancer treatment. No specific complimentary or alternative therapy has been proven beneficial, but many adjunctive treatments have been tried. Compounds such as curcumin, the principle ingredient in turmeric, have shown efficacy in nonhuman research and are being tested in clinical trials in pancreatic cancer. Given the modest benefit derived from chemotherapy and radiation in this disease, alternative approaches in the treatment of pancreatic cancer in conjunction with (rather than instead of) standard treatment is warranted.

Is it possible to prevent pancreatic cancer?

At this time, there is no known surveillance strategy to reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer for the general population. With only 48,900 new diagnoses a year, screening blood tests or X-rays have never been proven to be cost effective or beneficial. Additionally, doctors do not routinely screen individuals with family members diagnosed with pancreatic cancer aside from the rare instance where a known genetic risk factor is present.